Julia Child’s love affair with kitchen tools lasted for as long as she lived. She was keen to try new devices for her own enlightenment but also felt a responsibility to her television viewers and live cooking demo audiences to “try out everything new so that I can have a valid opinion of its worth.” Where in her kitchen to store everything new was already an issue for Julia in 1976, when she admitted, “even I have almost come to the point where any further acquisition must mean the getting rid of an existing object, and that is a terrible wrench, because I love almost every piece.”

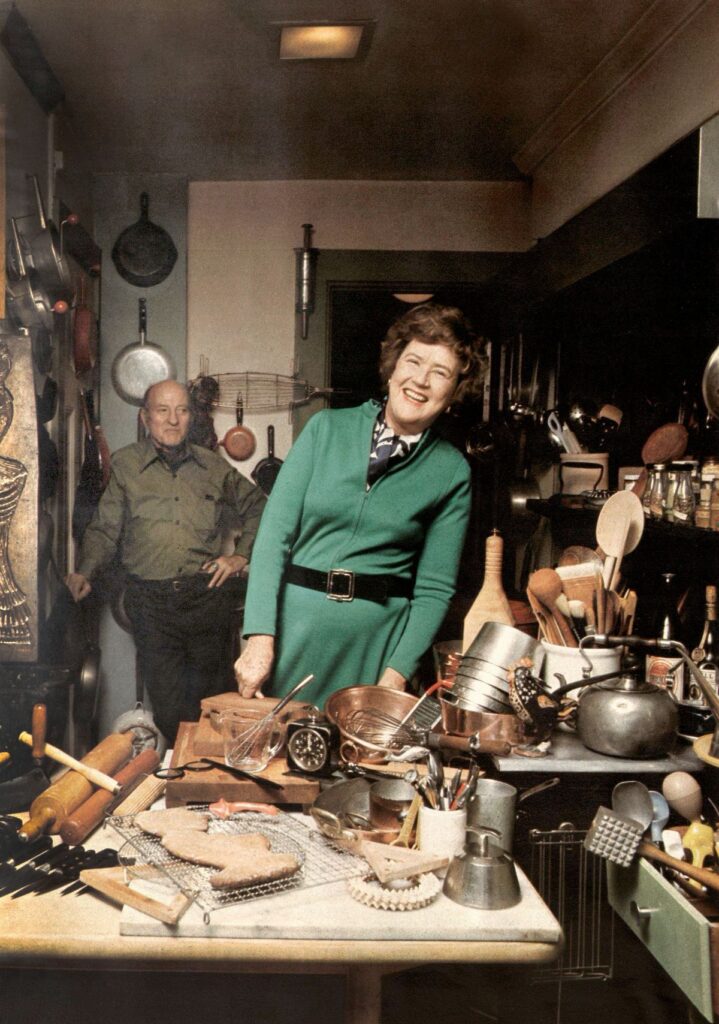

On principle, Julia steadfastly refused to represent any particular brand of cookware, but she gave credit when credit was due, lauding types of equipment—like the sturdy stand mixer and food processor—that revolutionized kitchen work. Over four decades, her Cambridge, Massachusetts, kitchen absorbed an astonishing number of tools, equipment, gadgets and artwork, most of which she managed to fit within the basic design created by her husband, Paul Child, in the early 1960s. Paul mused that Julia had enough equipment “to stock two medium-sized restaurants,” while she graciously praised his original design by declaring how it allowed for expansion without the kitchen taking on the junk-shop look that she was determined to avoid.

The National Museum of American History collected Julia’s kitchen in 2001, and it has been on view for much of the past two decades. Since 2012, it has served as the cornerstone of our exhibition “Food: Transforming the American Table.” As one of the staffers who met with Julia to discuss the kitchen donation and to record her thoughts on its history, I have spent considerable time delving deeply into the stories behind this marvelous room. I have had the joy and benefit of learning from and alongside my museum colleagues as we examined more than 1,000 objects that we collected and together created exhibitions and programs that have placed Julia and her kitchen into the larger context of American social and cultural history.

But I must confess that cooking had never been my passion—staying out of the kitchen was my goal as a college student in the 1970s, when supporting the Equal Rights Amendment and the National Organization for Women appealed to my idea of a path to a bright future that could somehow accommodate my ambitions for a career outside of the home. But after moving from the Midwest to the East Coast and entering the museum field in 1981, I became more aware of how food and culture intersected. The worlds that opened up by experiencing a variety of cuisines, plus the allure of fine dining and the sensory jolt from encountering truly fresh ingredients, awakened something that had lain dormant.

Then, whomp! Our friend Debora gave my husband and me an unexpected wedding present: a copy of Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume One—a serious tome if ever there was one. Curious, we started in with boeuf bourguignon, the first dish Julia prepared on her television series, “The French Chef,” in 1963. Transformational. We gingerly moved on to other recipes, as if we were taking a course on cooking. And of course, we were, not realizing that we were part of a large cohort of Americans who were adjusting their thinking about food and cooking.

As the years have gone by and especially since meeting Julia and collecting her entire home kitchen, I have found that her message about being open to trying new recipes and cuisines—and enjoying the social and creative process of cooking—resonated even with me. As I came to know more about her and her culinary legacy, as well as how she lived her life fully and with unwavering passion, I have embraced the vast universe of food history and culture.

This universe includes cookware, recipes, kitchen design, cooking techniques, food memories and larger issues of food systems, health and access that I would have dismissed in my youthful focus on a professional identity outside of the domestic sphere. What I didn’t realize then was that Julia had flipped the script: Her home kitchen—that domestic place—was the rigorously professional space that launched, nurtured and made possible her remarkable career.

Julia Child in the kitchen Paul Child / © Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, President and Fellows of Harvard College/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/db/01/db01c480-f86a-485e-b262-3ffb4f26b1be/juliachildskitchen_p005a.jpg)

Neither a junk shop nor a collection of restaurant ware, Julia’s home kitchen speaks to and reflects some of the major transformations in food that characterize the second half of the 20th century in the United States. This way of understanding the historical context of the kitchen can be observed in old and new technologies and by recognizing the remarkable range of materials present, from copper to cast iron, from stainless steel to plastics. What’s more, the manner in which common kitchen tools share space with highly specialized, professional equipment evokes a sense of time and place as well as Julia’s embrace of devices that got the job done. It is important to keep in mind that Julia’s open and fearless approach to cooking, teaching and learning came together at a time when more—certainly not all—Americans had weathered the deprivations of the Great Depression and World War II and had both the means and interest.

In the years following World War II, food production in the United States expanded to meet the national goals of an abundant and affordable food supply, ushering in a more industrialized, centralized, highly processed, aggressively advertised and hyperglobalized system. As food industries and popular media encouraged women to forsake cooking at home and to let processed, convenience and fast foods relieve the drudgery of the kitchen, individuals like James Beard, Joyce Chen, Edna Lewis, Marcella Hazan, Alice Waters and of course Julia Child represented another approach to food, cooking and feeding oneself and others. With her enthusiasm for learning and encouraging others to experience new foods and flavors, Julia brought people toward a way of thinking about food and cooking that contradicted many of the popular and powerful voices of industry.

For Julia and others, “convenient, easy and cheap” were not the three most essential guiding principles for getting dinner on the table. Yet she understood that home cooks often desperately needed time-saving devices and culinary shortcuts. Their lives, she knew, revolved around raising children and accommodating their activities, managing a household, perhaps juggling paid work outside of the home, and typically doing so without help.

Below are five (plus a few dozen) tools and technologies that Julia Child tested and used in her kitchen.

Crock-Pot

A booklet of recipes and instructions accompanied the original Rival Crock-Pot. Smithsonian collections photography, Jaclyn Nash / National Museum of American History/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/82/ea/82eae982-6eed-42e1-8e5d-237f84814b75/juliachildskitchen_crockpotmanual_p121a.jpg)

For many American home cooks, the Crock-Pot, introduced by the Rival Manufacturing Company in 1971, was a lifesaver. Electric slow cookers had been available since 1950, when the inventor Irving Naxon began manufacturing his Naxon Beanery in Chicago, ten years after receiving a patent for the device. Naxon eventually sold his business to the Rival Manufacturing Company in Kansas City, Missouri, and after some design alterations and fueled by a robust marketing campaign, the Rival model caught the attention of those looking for an easy way to prepare a home-cooked meal while they were busy elsewhere, including at paid employment outside of the home. The advertising tagline “Cooks all day while the cook’s away” was an appealing idea for many women who had entered the workforce to pursue careers or to help provide financial support for their families.

With Julia’s penchant for new kitchen equipment, the question arises as to whether she was among those who tried the electric Crock-Pot in the ’70s. A partial answer is found in the archives at Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library: In 1978, Julia purchased two slow cookers, one from Dickson Brothers Company, in Cambridge, and another from France, for her “experiments.”

Julia also wrote about cooking baked beans in an electric Crock-Pot in a chapter on potluck suppers in her late 1970s book, Julia Child & Company. She noted that she had better results if she precooked the beans and sautéed the onions and pork before putting everything into the Crock-Pot to finish cooking slowly.

Food processor

Julia kept her food processor and blender on the top of the butcher block table. Smithsonian collections photography, Jaclyn Nash / National Museum of American History/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/85/38/8538028d-7a9a-476a-aaa9-d347b4227150/juliachildskitchen_foodprocessor_p135a.jpg)

Julia was tremendously interested in new technologies for the kitchen, perhaps none more so than the electric food processor. She was keen to try out the different models that were coming on the market. After a 1972 conversation with James Beard, the American chef, cookbook author and culinary expert who became a lifelong friend of Julia’s at the time of Mastering the Art of French Cooking’s publication, Julia wrote to a Mrs. Wilson at Robot-Coupe USA asking for literature on the new Robot-Coupe vertical cutter-mixer. Manufactured in France, the Robot-Coupe promised to cut raw meat, shred and slice vegetables, chop nuts, and perform various other tasks that were done by hand in home and commercial kitchens alike. Beard had already ordered a unit, and Julia was curious to know about the sizes, prices and availability of the Robot-Coupe in the United States.

She also corresponded with distributors of the Moulinex Moulinette electric chopper (a compact chopper and mincer). By 1978, she counted some 22 different brands of food processor on the market and had tested about eight of them. She told a correspondent that she couldn’t recommend any one model as she “wouldn’t care to be stuck for the consequences!”

She did, however, list the models she had used and found to be satisfactory: Cuisinart, Farberware, Norelco, Sunbeam and Waring.

Although she wouldn’t declare her favorite brand, Julia did not downplay her exuberance over the technology. She advised readers of McCall’s magazine that they should ask “Santa for a food processor.”

She declared:

“The food processor is the first revolutionary new kitchen dog-work machine to appear since the electric mixer and the blender, and while it does both mixing and blending, it also chops parsley and onions (which the blender does with difficulty); slices carrots, potatoes, cucumbers or what have you; juliennes mushrooms and other items; grates cheese, grinds meat, purees fish, makes mayonnaise and pie crust doughs and even cake batters. In fact, it is generally about the most useful machine a good cook—or even a semi-non-cook—can have in the kitchen since by taking so much of the time and drudgery out of many otherwise arduous operations it actually makes good cooking possible in a way it never was before.”

Microwave

This 1955 Tappan RL-1 microwave oven (not the same machine used by Julia in her kitchen) is in the collections of the National Museum of American History. Richard W. Strauss / National Museum of American History/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/13/f5/13f590b7-721e-4569-af30-36c583b14097/juliachildskitchen_microwave_p119a.jpg)

The introduction of the microwave oven for home use in 1955 wasn’t exactly a rousing success. The Tappan RL-1 electronic model microwave oven was expensive—$1,295, over $15,000 today—and large—the size of a modern mini fridge, at ten cubic feet (27 by 24 by 27 inches). The inventors hoped it would replace regular ovens, and they designed the unit to resemble a regular stove, building a recipe drawer into the housing and publishing cookbooks with sumptuous-looking meals on the covers. The technology, developed during World War II, was not well understood or trusted by consumers, especially arriving on the scene to cook their food as the Cold War was itself heating up and fears of radiation were at a fever pitch.

By the ’70s, microwave ovens were much smaller and more affordable—about $300 in 1976—and at some point, Julia and Paul invested in what she called “this NASA machine,” a moniker recalled by her great-nephew Alex Prud’homme. He continued: “Julia was a fast-forward type of person and she didn’t always take time to read instructions. I didn’t witness this, but in the early version of the microwave, [it was] an enormous machine. She put a frozen chicken, some green beans and a piece of chocolate cake [inside], thinking that one [would] tap the buttons and it would miraculously cook everything. And, of course, the thing rattled, made all this noise, chocolate dripping out of the door. She opened it up—half-frozen chicken, etc. [and said], ‘Oh, I guess that didn’t work!’”

Famously, she also used the microwave oven to dry off a newspaper that had gotten wet in the rain, a mistake that set the unit afire. Later, Julia remarked that she had two freezers and used the microwave for defrosting and heating chicken stock, for melting butter, heating up milk or tea and melting chocolate, but not for cooking a meal. Although many people touted the microwave for baking potatoes quickly, she preferred baking them in her oven. Like other cooks and consumers, Julia figured out how this new technology could enhance her cooking, not take it over.

Rolling pins

Three different types of rolling pins Smithsonian collections photography, Jaclyn Nash / National Museum of American History/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b3/c5/b3c592ac-6698-4af0-b5a6-dfdc3fd314d4/juliachildskitchen_rollingpins_p145a.jpg)

Julia made her assessment of ordinary rolling pins sold to American consumers brutally clear. In an early episode of “The French Chef,” she held up a standard rolling pin and, in a dramatic flourish, tossed it to the side, calling it “a silly kind of a pin to have!” The pin landed in the wastebasket, and Julia never bothered to retrieve it, as she found it utterly without merit.

Instead, Julia encouraged her viewers to invest in heavier and longer pins that would help them roll out dough for pies and puff pastry. She found what she called the “Cheshire pin,” made in Cheshire, Connecticut, “perfect because it’s heavy enough, it does half the work for you.” A “typical French rolling pin” without handles was declared “nicer than most because it was [made of] olive wood.” Another pin, tapered at the ends, found favor, as did the ribbed pin for making French puff pastry, because the edges break up the butter and smooth out the dough.

Julia’s statement about the importance of rolling pins was underscored by how she cared for and displayed them. She stored her pins in a large copper stockpot, which was typically kept in the pastry pantry adjacent to the kitchen. The visual appeal of the gleaming pot holding Julia’s impressive array of rolling pins and other long tools such as dowels, skewers and long-handled forks accounted for its movement onto countertops in the kitchen proper as a favorite backdrop for photography and television.

Buffalo iron

One of two buffalo irons in Julia’s kitchen Smithsonian collections photography, Jaclyn Nash / National Museum of American History/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/26/80/26809942-ffb9-4df2-9b0f-78ed45f94921/juliachildskitchen_buffaloiron_p149a.jpg)

Julia learned how to cook green beans without losing their vibrant color from the chef Max Bugnard, her French instructor at Le Cordon Bleu. While working aboard trans-Atlantic steamships as a young man, he observed a chef dropping green beans into a huge cauldron of boiling water, then plunging a red-hot poker into the water to return the boil quickly. The rest of the process adhered to the classical method of blanching the beans by cooking them for two to three minutes and then immersing them in an ice bath. Julia mentioned this to Sherman Kent (a friend who had sold her a six-burner Garland range and whom she called “Old Buffalo”), and he made her an iron, which she named after him. The buffalo iron hangs from the hood of the range.

Julia’s longtime friend and Oklahoma chef John Bennett told a story of making dinner for Julia and Paul in their Cambridge kitchen in 1962, explaining how the buffalo iron was used in creating a memorable meal using Julia’s recipes. He also revealed the unfettered enthusiasm that young chefs brought to an opportunity to cook in Julia’s kitchen, just when she was gaining prominence among culinary professionals.

Bennett recalled:

“We made spinach with a buffalo iron, which was a large heavy piece of iron heated red-hot that’s plunged into the spinach water to bring it back to a roaring boil to keep the spinach green. We then cooled the spinach, squeezed it dry, chopped it, then tossed it with shallots, garlic and nutmeg in lots of brown butter.

We prepared strip sirloin in a well-seasoned black cast-iron skillet, Diane style, accompanied by Gratin Dauphinoise potatoes. …

From the book [Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume One], we made Charlotte Malakoff with strawberries, homemade ladyfingers, almonds and lots of butter generously flavored with Grand Marnier, molded and chilled to be served with a fresh strawberry sauce.”

And many more gadgets

Various kitchen tools used to cut, shape, open, spread, pull and grab Smithsonian collections photography, Jaclyn Nash / National Museum of American History/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/f5/c4f5ce3d-cdbf-4a12-8c41-23f9bb83dc10/juliachildskitchen_gadgets_p154-155.jpg)

“I’ve always been a gadget freak, and some things are just wonderful!”

When Julia made this confession, she was referring to an array of hand tools designed for specific tasks. She kept most of these gadgets in drawers that were easily accessible to work surfaces such as the countertops, the Garland range and the kitchen table. Julia collected different designs of certain gadget categories, such as knives for opening shellfish, and acquired many others in the spirit of experimentation. She also received gifts of gadgets, some of them homemade, from friends and admirers alike. A full four drawers in the kitchen contained gadgets to cut, shape, open, clean, pull and grab—all necessary in kitchen work.

Reprinted from the new book Julia Child’s Kitchen: The Design, Tools, Stories and Legacy of an Iconic Space by Paula J. Johnson. Copyright (c) 2024, Smithsonian Institution; copyright (c) 2024, The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts. Published by Abrams.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JN2018-00020_resized.jpg)